By Lina Federiko

Gap

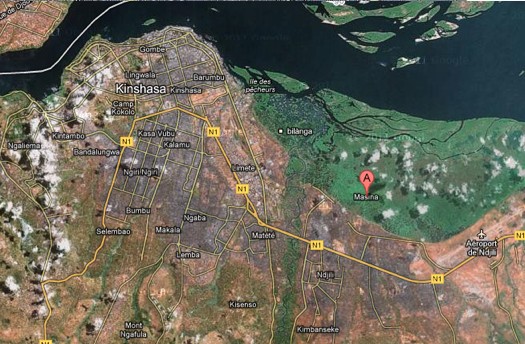

Masina slum is located in southeast region of Kinshasa, the capital of Democratic Republic of Congo. Kinshasa lies on the left bank of Congo River (Lateef, 2010). Masina is located far from the river and economic activity, and borders wetlands to the north. The city spreads over an area of 9,965 square kilometers, of which only 650 square kilometers is urbanized (Lateef, 2010). Masina takes up approximately 20-25% of the total city area.

The current population of Kinshasa is 8.7 million, and it is the fastest growing city in Africa, followed by Lagos (UN Habitat, 2010). Approximately half of Kinshasa’s population lives in slums, 300,000 are considered higher income (BBC, 2010), and the remaining live below the poverty line (UN Habitat, 2007). Population density is approximately 13,384 people per square kilometer. 54% of city inhabitants don’t have access to clean water (UN Habitat, 2010).

Informal sector in Kinshasa provides more than 90% of all public transport services, household waste collection, construction workers, plumbing and mechanical repairs, and 90% of share in local trade (UN Habitat & UNEP, 2010, p. 182).

Coping

To cope with constant delays in pay, civil servants in Kinshasa are pocketing municipal income by issuing fake receipts, and diverting the fees from municipal treasury (UN Habitat, 2010). Slum dwellers spend up to 74% of income on food (UN Habitat & UNEP, 2010, p. 181).

Kinshasa’s slum dwellers rely heavily on timber and charcoal for household use or trade at informal markets. (UNEP, 2012). Only 42% of population in Kinshasa has access to sanitation services (USAID, 2008). Slum dwellers create ‘flying toilets’, which involves throwing plastic bags full of human waste onto rooftops, in response to the lack of proper sewage system in slum settlements (Connor, 2006).

Response

Local government should construct a comprehensive sewage system for the city of Kinshasa as it will benefit households and firms through better public health. The city can finance infrastructure through combination of market borrowing, taxes, user fees and grants. Taxes can be levied on new infrastructure development, to capture externalities of infrastructure investments (Fessy, 2011).

Secondly, the local government of Kinshasa should utilize land-use and zoning laws as well as enforce property rights. This is expected to reduce informal competition and feuding over land rights, secure land for affordable housing, and secure property rights of land owners. As the city population continues to grow, so is the strive to develop land. Including Kinshasa’s poor population, particularly slum dwellers, in the process is essential. A key recommendation is to formalize land transactions to eliminate corruption and exclusion of poor inhabitants.

This article is a product of Professor Shagun Mehrotra’s Global Urban Environmental Policy class. Views expressed are entirely those of the individual author.

References

Connor, N. (2006, April). Unsustainable Cities. The Brooklyn Rail Online Publication. Article retrieved on February 1, 2012. Retrieved from http://brooklynrail.org/2006/04/express/unsustainable-cities.

Fessy, T. (2011, August 20). Congo River luxury condos cause Kinshasa controversy. BBC News. Article retrieved on February 6, 2012. Retrieved from http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-14595625.

Google. (2012). Google Earth (Version 6.0.3.2197) [Software]. Available from http://www.earth.google.com

Lateef, A. S. A., Fernandez-Alonzo, M., Tack, L., & Delvaux, D. 2010. Geological constraints on urban sustainability, Kinshasa City, Democratic Republic of Congo. Publication retrieved on February 5, 2012. Retrieved from http://eg.geoscienceworld.org/content/17/1/17/F11.expansion.

United Nations Environmetal Programme (UNEP). (2012, February 6). Democratic Republic of the Congo. Retrieved from UNEP webpage http://postconflict.unep.ch/congo/en/content/kinshasa-wood-collectors.

UN Habitat. (2010). Population of African Cities to Triple. The State of African Cities 2010. Retrieved on January 30, 2012. Retrieved from UN Habitat webpage http://www.unhabitat.org/content.asp?cid=9187&catid=5&typeid=6.

UN Habitat. (2007, April). Three things we should know about slums. Retrieved on February 6, 2012. Retrieved from UN Habitat publication database www.unhabitat.org/…/4625_34413_ GC%2021%203%20Things%20to%20know%20about%20slums.pdf.

UN Habitat & United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP). (2010). The State of African Cities 2010: Governance, Inequality and Urban Land Markets. Retrieved on January 30, 2012. Retrieved from UN Habitat publication database, www.unhabitat.org/pmss/listItemDetails.aspx?publicationID=3034.

United States Agency for International Development (USAID). (2008). Democratic Republic of the Congo: Water and Sanitation Profile. Retrieved on January 30, 2012. Retrieved from USAID database, http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PNADO929.pdf

This article is a product of Professor Shagun Mehrotra’s Global Urban Environmental Policy class. Views expressed are entirely those of the individual author.